- Introduction

- Resource Review

- Sampling and Methodology

- Research Questions

- Virginia Policing Trends

- Analysis of Research Questions

- How do traffic stops vary across localities?

- How do traffic stops vary across the target localities?

- Within specific localities, what actions were taken after a police stop?

- Within specific localities, what are the demographic characteristics of who is getting stoppped and who is getting arrested?

- Conclusion

- References

Police Stops Analysis

Owayne Owens, Lily Slonim & Ramya Tella

May 4, 2023

Introduction

This project examines policing patterns across the state of Virginia, through the lens of police stops. Racially selective practices have shaped dominant forms of traffic enforcement across the United States, where empirical scholarship on the subject has clearly indicated that black and Hispanic drivers are substantially more likely to be searched when stopped relative to white drivers. Past research has also indicated that the race of the officer in charge of the stop has a role to play in the outcome (Fagan and Geller, 2020).

Importantly, Virginia has been home to the passage of legislation that expressly curtails the power of the police to engage in arbitrary actions that amount to ‘pretextual stops’ (Haywood, 2022). Recent research claims that this legislation has played an important role in reducing the number of police interactions relating to common and specific pretexts of marijuana odor, equipment violations, and jaywalking (ibid.).

These findings have been accompanied by an expansion in data-informed undertakings such as the Stanford Open Policing Project which provides a comprehensive, statistically robust analysis of policing patterns across the country. The findings of this project have been that while driver behavior plays a role in the occurrence of police stops, racial bias may also have a significant part to play (Pierson et al., 2020).

Resource Review

Three sources informed our project questions, analysis and visualizations, Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed America Freedom by Sarah Soe, the Stop-And-Frisk Data Report published by the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), and the Sandford Open Policing Project. Examinations of these sources and their role in the project are below.

Seo, Sarah A.. Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Seo explores the relationship between the rise of automobiles as a dominant form of transportation and the rise of policing. Seo uses a historical approach to detail specific instances in the legal and political history of the United States that enabled an expansion of police powers vis-a-vis the automobile. The mass production of automobiles made them more affordable for citizens to purchase and cars quickly became the dominant mode of transportation for many across the United States. However, the large-scale adoption of vehicles intersected with an intensification of discretionary policing, with origins in Prohibition era car searches.

Over time, police searches assumed an explicitly racial aspect where the mere suspicion of police officers regarding wrongdoing constituted a sufficient reason to stop and search drivers. Coupled with the increasing injuries and fatalities resulting from the sheer volume of automobiles on the roads, local governments turned to the expansion of their forces as the answer to a complex challenge. As Seo examines the police state in relation to cars, Seo contemplates the practical, theoretical, and legal problems of policing everyone who drives, especially populations with increased police surveillance. Over-policing is a current reality for people of color who are confronted with violence every day. Our project has benefited from the contextual framework provided by Seo to examine how the reasons for, and nature of, policing disproportionately affects specific demographic groups.

NYCLU. 2018. “Stop-And-Frisk Data.” New York Civil Liberties Union. December 10, 2018. https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data.

The primary objective of the Stop-And-Frisk Data report is to provide an analysis of New York City’s stop-and-frisk data from 2002-2021. The findings of the report include:

- Increasing the rate of police stops does not enhance safety. The report found no evidence that ramping up stops made New Yorkers safer.

- The majority of the stops are among people of color, with some of these stops leading to violent police misconduct.

- There is a significant decrease in reported stops starting in 2011, which coincides with the beginning of the De Blasio administration.

- Though the overall number of stops has decreased significantly, the arrest rate increased under the new Mayoral Administration.

This source was used as an exemplary model for how we can produce effective visuals and communicate the findings of the police stop data in our project. Many of the visualizations produced in our project were inspired by the report.

Stanford Open Policing Project, 2015-present. https://openpolicing.stanford.edu/

The Stanford Open Policing Project was started with the objective of providing a comprehensive analysis of traffic stops with a focus on demographic information. The researchers have shown that this can often be challenging owing to the lack of a standardized template for the recording of stop and search data.

They make use of data from 50 patrol agencies and municipal police departments to show that there is a significant racial bias in the discharge of policing duties. Statistical analysis of data revealed that individuals belonging to racial and ethnic minorities were stopped far more often per 100 stops, than white drivers. The project provides important visualizations of actions before and after the stop and shows that minority drivers tend to be searched more frequently than white drivers when stopped. The researchers also employed an outcome test to determine whether discrimination played a role in the decision to search.

The approach of contextualizing demographic indicators per 100 stops is a lens that may have applicability to our project. The Stanford Project provides a basis for the study of the discriminatory nature of police stops by also conducting a statistical analysis to test the validity of the hypothesis. Additionally, their use of engaging forms of visual and textual representation can be a useful cue for how our project might ultimately look.

Sampling and Methodology

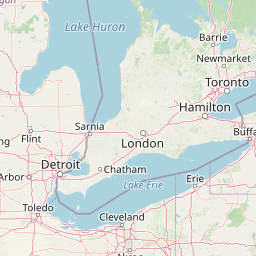

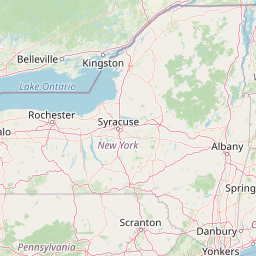

This project has been designed to provide a deeper understanding of the factors constituting police stops with a view to engaging in a critical analysis of the distribution of demographic trends. We have drawn on the presentational format of the Stanford Open Policing Project and the NYCLU stop-and-frisk project (NYCLU, 2022) to focus on the state of Virginia through the data-informed stories of four counties that have varying distributions of police stops that are both related and unrelated to demographic characteristics. Chesterfield County, Fairfax County, Henrico County, and Virginia Beach City were initially selected because the localities had the highest traffic stops in Virginia between 2020 - 2022. Upon additional research, the team found news reports that further compelled the team to examine the selected counties. The relevant news reports are below:

- Chesterfield County, which saw a dramatic uptick in police stops in mid-2022, resulting in the issuance of over 500 tickets for offenses related to speeding, reckless driving, cell phone use and driving without a license (NBC12, 2022).

- Fairfax County, which has been the subject of media reports on racial profiling and drug-related stops in 2022 (Carey, 2022).

- Henrico County, which was the location of the death of Irvo Otieno, an African American resident, at the hands of law enforcement in 2023 (Rizzo et al., 2023).

- Virginia Beach City, which has been the subject of violent police stops between 2022 and 2023 (Burchett, 2022).

The project accessed datasets from three primary data sources. Data were retrieved from the Virginia Open Data portal, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), and the U.S. Census Bureau. The community policing dataset was downloaded from the Virginia Open Data portal. This dataset details all traffic stops in Virginia between July 2020 - December 2022, reported by the Virginia Department of State Police. Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT) by locality datasets were downloaded from VDOT. These datasets estimate the total traffic volume measured by VDOT. The project includes DVMT by locality for 2020 and 2021. As of April 2023, the 2022 DVMT dataset is not published. TIGER Shapefiles and population data were downloaded through the U.S. Census Bureau. The Shapefiles provided geometry for each locality in Virginia to be able to conduct spatial analysis. Total population and population by race were both published in the 2021 American Community Survey.

The development of this project has proceeded through the following steps that illustrate the data-wrangling efforts undertaken by the team to produce meaningful visual analyses of the observed patterns.

- First, the team reformatted columns in the community policing dataset. The date column was reformatted to develop new date measures, including separate columns for ‘incident_year’ and ‘incident_month.’ These new measures allowed the team to visualize trends over time and overcome the challenge of working with undifferentiated data. The values within the ‘race’ and ‘action_taken’ columns were renamed to shorten the character count of each value. The ‘locality’ column was also reformatted to ensure the values mirrored the names in the Tiger Shapefile dataset.

- Second, the team calculated the total number of police stops and arrests across the state by year. These metrics were calculated through the ‘group_by’ and ‘count’ functions.

- Third, the team calculated ‘Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT’ through a

multi-step process.

- The number of police stops by year and locality was calculated. These metrics were calculated through the ‘group_by’ and ‘count’ functions.

- Three separate datasets were created, police stops by locality for 2020, police stops by locality for 2021, and police stops by locality for 2022. The three datasets were joined to the TIGER Shapefile dataset using the ‘locality’ field. Then, these files were joined with their respective DVMT datasets using the ‘locality’ column. Police stops by locality for 2020 was joined to the 2020 DVMT, police stops by locality for 2021 was joined to the 2021 DVMT, and police stops by locality for 2022 was joined to the 2021 DVMT. As of April 2023, the 2022 DVMT dataset has not been published. Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated by dividing the total number of police stops by the DVMT. Then, this number was multiplied by 1000.

- Lastly, these files were combined into one larger file using ‘rbind’.

- Once the initial data-wrangling stage was complete, a report was created as the final work product. The report is composed of graphs, interactive maps, and a table. The graphs were developed using ggplot2, the interactive maps were developed using leaflet, and the table was developed using datatable.

While Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT provides an understanding of traffic stops compared to traffic volume, there are a few limitations with the metric. The community policing data only started in July 2020, however, the DVMT is calculated by year. Therefore, the 2020 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT only contain half a year of police stops, but a full year of estimated traffic volume. Another limitation is that the 2022 DVMT is not published. The 2022 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated using 2021 DVMT. There was likely a higher rate of travel in 2022 compared to 2021 because the threat of COVID-19 decreased. Therefore, the 2022 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT could be inflated when using the 2021 DVMT.

Research Questions

The project is centered around the following questions:

- How do traffic stops vary across localities in Virginia?

- How do traffic stops vary across the target localities?

- Within the target localities, what actions were taken after a police stop?

- Within the target localities, what are the demographic characteristics of who is getting stopped and who is getting arrested?

Virginia Policing Trends

The community policing dataset reflects all traffic stops in Virginia between July 2020 - December 2022, reported by the Virginia Department of State Police. Policing trends in Virginia are analyzed by month and year to provide a more accurate comparison between years.

The stops for 2020 rose dramatically by over 70,000 between July and November. The number of police stops across the state are consistently above 50,000 between January and December in 2021 and 2022. It is essential to understand the spatial distribution of these events within the state to arrive at a clear inference of the frequency of stops within specific localities and what the causes for these may be.

The data shows that the number of stop-related arrests was highest in July 2020 and 2021. The study years show more arrests in the summer months (June - August) than in December. Importantly, 2022 is characterized by uniformly high arrest numbers of over 1,000. A further examination of causative factors is needed.

Analyzing stops and arrests provides a better understanding of temporal policing patterns in Virginia. December and January both tend to be months with a low number of police stops and arrests across all years. In 2020, July had the highest number of arrests for the year, but the lowest number of police stops. In 2021, a large increase in arrests happened between June to July. A similar pattern occurred during these same months for the number of stops; as the number of police stops increased, the number of arrests increased. The police stop and arrest trends are somewhat similar across the months of 2022. For instance, January 2022 has a low number of police stops and arrests, while March has a high number of police stops and arrests.

- How do we measure this? Police stops and arrests are the sum of the total number of police stops and arrests across all localities in Virginia by year.

- Data Source: Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to-December-31/2c96-texw

Analysis of Research Questions

How do traffic stops vary across localities?

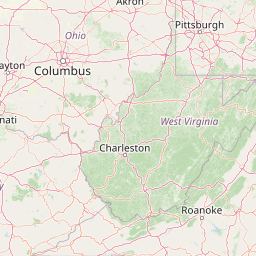

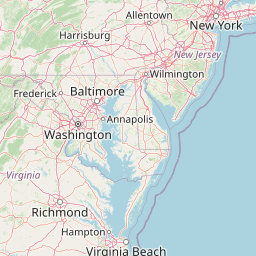

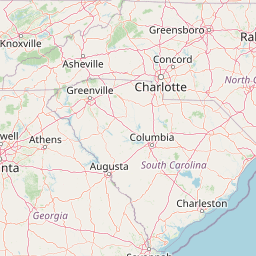

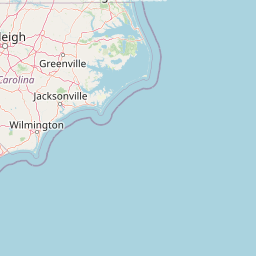

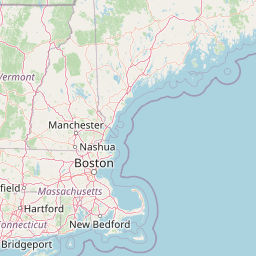

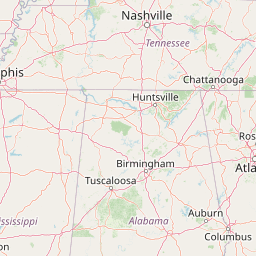

Chesterfield County, Fairfax County, Henrico County, and Virginia Beach City consistently had the highest traffic stop count in Virginia between 2020 - 2022. Prince William County and Loudoun County also had high numbers of traffic stops. These localities likely have the highest volume of traffic stops because they are densely populated. The total number of stops is more reflective of the total population rather than a disproportionate number of stops.

While examining the volume of traffic stops provides context into where the highest number of stops are happening, it does not allow researchers to understand where a disproportionate number of stops are occurring. Police Stop per 1,000 DVMT controls for traffic volume, providing a more accurate understanding of where a disproportionate amount of stops are happening. The data show that Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT is related to counties with major corridors. In 2020 and 2021, Emporia City, Northampton County, Manassas Park City, and Hopewell City had the highest Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT. In 2022, Manassas Park City, Hopeful City, Emporia City, and Falls Church City had the highest Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT. These localities are all near major highways. I-95 bisects Emporia City, US 13 bisects Northampton County, State Route 28 bisects Manassas Park City, Manassas Park City is next to I-66, I-296 is next to Hopewell County, State Route 10 bisects Hopewell County, and State Route 7 bisects Falls Church City and Falls Church City is next to I-66. Therefore, it is likely that a majority of these stops are happening along or near these major corridors.

- How do we measure this?

- Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated by dividing the

total number of police stops by the Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT).

Then, this number was multiplied by 1000.

- 2020 police stops by locality was divided by 2020 DVMT, 2021 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT, and 2022 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT.

- The 2022 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT is calculated using 2021 DVMT because the 2022 data has not been published.

- The 2020 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT reflect a full year of DVMT, but only half a year of stop data.

- Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT) is an estimate traffic count calculated by VDOT.

- Police Stops is the sum of all police stops by locality and year.

- Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated by dividing the

total number of police stops by the Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT).

Then, this number was multiplied by 1000.

- Data Sources:

- Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to -December-31/2c96-texw

- U.S. Census Bureau,TIGER/Line Shapefiles, Virginia. https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-line-file.html

- Virginia Department of Transportation, “Traffic Data: Official AADT and VMT Publications” 2020-2021.https://www.virginiadot.org/info/ct-TrafficCounts.asp

Police Stop & Travel Patterns by Locality & Year, 2020-2022

- How do we measure this?

- Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated by dividing the

total number of police stops by the Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT).

Then, this number was multiplied by 1000.

- 2020 police stops by locality was divided by 2020 DVMT, 2021 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT, and 2022 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT.

- The 2022 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT is calculated using 2021 DVMT because the 2022 data has not been published.

- The 2020 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT reflect a full year of DVMT, but only half a year of stop data.

- Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT) is an estimate traffic count calculated by VDOT

- Police Stops is the sum of all police stops by locality and year.

- Total Population reflects the total 2021 population estimates as measured by the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey

- Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT was calculated by dividing the

total number of police stops by the Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT).

Then, this number was multiplied by 1000.

- Data Sources:

- Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to -December-31/2c96-texw

- Virginia Department of Transportation, “Traffic Data: Official AADT and VMT Publications” 2020-2021.https://www.virginiadot.org/info/ct-TrafficCounts.asp

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-year estimates, ’Age and Sex (S0101).’2021. https://data.census.gov/table?q=population&tid=ACSST1Y2021.S0101

How do traffic stops vary across the target localities?

Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT Comparison Across Localities

Target localities were selected for the project for further analysis. The selection requirements included a high volume of police stops between 2020 - 2022 and relevant events within the localities related to traffic stops.

The data show Virginia Beach City as the locality with the highest Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT across the study years. Virginia Beach City has a large number of police stops, and Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT. Therefore, the prevalence of traffic stops in Virginia Beach City is higher than in other localities. Chesterfield County and Henrico County both follow close behind Virginia Beach City. Fairfax County has the lowest Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT by comparison across the study years. Within the selected localities, Fairfax County has the highest DVMT, and the highest number of police stops across the study years. While it is important to analyze localities with a high number of traffic stops, it is important to note that the likelihood of each driver getting stopped is lower than in localities with higher Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT.

- How do we measure this? Police Stops per 1,000

DVMT was calculated by dividing the total number of police stops by

the Daily Vehicle Miles Traveled (DVMT). Then, this number was

multiplied by 1000.

- 2020 police stops by locality was divided by 2020 DVMT, 2021 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT, and 2022 police stops by locality was divided by 2021 DVMT.

- The 2022 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT is calculated using 2021 DVMT because the 2022 data has not been published.

- The 2020 Police Stops per 1,000 DVMT reflect a full year of DVMT, but only half a year of stop data.

- Data Sources:

- Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to -December-31/2c96-texw

- Virginia Department of Transportation, “Traffic Data: Official AADT and VMT Publications” 2020-2021.https://www.virginiadot.org/info/ct-TrafficCounts.asp

Within specific localities, what actions were taken after a police stop?

Chesterfield County: The data illustrate that citations and summons constitute a substantial percentage of the total actions taken. While the percentage of arrests remain uniformly low relative to citations which show an increasing trend between 2020, and 2021 and 2022. The decision of the officer to not take an enforcement action follows a decreasing trend over the study years.

Fairfax County: The data illustrate a decreasing trend for arrests between 2020 and 2022. However, the percentage of citations and summons increase during this period and are substantially higher than what is observed in Chesterfield County.

Henrico County: The data illustrate a substantially increasing trend for arrests between 2020 and 2022, which is accompanied by a nearly proportional decrease in the percentage of citations and summons issued. Of all the selected counties, Henrico is the only locality displaying such an arrest trend.

Virginia Beach City: The data illustrate an increasing trend in arrests and citations and summons as well as an increase in the percentage of stops that do not result in an enforcement action. The percentage of warnings issued decreases across the study periods.

How do we measure this? We counted each category of action taken after a stop and used this amount as a proportion of the total count across all the different categories of action taken.

Data Source: Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to-December-31/2c96-texw

Within specific localities, what are the demographic characteristics of who is getting stoppped and who is getting arrested?

Before analyzing the demographic characteristics of traffic stops, we first wanted to examine the demographic characteristics within and across the selected localities. This ultimately informed our understanding of how stop and arrest trends compared to the population shares of specific demographic groups.

Demographic Data by Locality

- How do we measure this? From the 2021 Census data, we counted the total population for each locality then we counted the total for each racial category and have this total be represented as a proportion of the total population in each locality.

- Data Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-year estimates, “Race (B02001)”.2021. https://data.census.gov/table?q=B02001&y=2021

Chesterfield County: The percentage of white drivers stopped and arrested is roughly proportional to the share of African American drivers. The percentage of stops and arrests pertaining to Asian or Pacific Islander drivers is much lower by comparison. These trends offer cause for concern as the population shares of African American individuals and white individuals are approximately 25% and 70% indicating a far higher percentage of arrests (50%) for the former group relative to total population.

Fairfax County: The percentage of stops relating to Asian and Pacific Islander drivers as well as white drivers is substantially higher than in Chesterfield County. The percentage of stops leading to arrests decreases across the study period for African American drivers. The percentage of stops relative to the total population share is high for African American individuals as they constitute only 20% of the population but account for nearly 25% of the total arrests.

Henrico County: The percentage of stops specific to African American drivers shows an increasing trend over the study period and a higher percentage of arrests for the same period. The percentage of arrests relative to stops is lower for white drivers. Similar to the other counties discussed above, the proportion of arrests specific to African American individuals is over 50% relative to their total population share of 30%.

Virginia Beach City: Similar to Henrico County, a lower percentage of stops specific to African American drivers translates into a higher percentage of arrests. On the other hand, the outcomes related to white drivers indicate that despite a higher percentage of stops, these translate into a lower percentage of arrests. African American individuals in Virginia Beach City face a much higher percentage of arrests relative to their population share which are currently recorded as 50% and 20% respectively.

- How do we measure this?

- Frequency of Stops: We looked at the total amount of stops for our chosen localities, and counted the frequency of each racial category that was reported from each stop.

- Arrests: Using the stop frequency metric, we filtered for only those who got arrested after a stop and counted the frequency of each racial category reported.

- Data Source: Virginia Open Data Portal, “Community Policing Data July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022.” 2020 - 2022. https://data.virginia.gov/Public-Safety/Community-Policing-Data-July-1-2020-to-December-31/2c96-texw

Conclusion

This study has shown that there are important linkages between the occurrence of police stops and the underlying demographic characteristics of drivers. While it is challenging to establish the role of racial bias in the increasing police stops per 1,000 DVMT, the cases of Chesterfield County, Henrico County and Virginia Beach illustrate high arrest rates relative to police stops per 1000 DVMT specific to African American drivers. Based on the nature and volume of emerging media reportage on the subject of racially motivated stops and arrests in these counties between 2020 and 2022, there is a need for a deeper examination of how and why these patterns persist.

References

Burchett, C. (2022). Virginia Beach police release footage that shows officer fatally shoot man after Newtown Road traffic stop. The Virginian-Pilot. Accessed on April 12, 2023. https://www.pilotonline.com/news/crime/vp-nw-police-shooting-newtown-20221205-prlhva2ttzgopmj5on4xtokvwq-story.html

Carey, J. (2022). Mom Demands Apology From Fairfax County Police After She Was Mistakenly Detained. NBC Washington. Accessed on April 12, 2023. https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/mom-demands-apology-from-fairfax-county-police-after-she-was-mistakenly-detained/3172877/

Fagan, J., & Geller, A. (2020). Profiling and consent: Stops, searches, and seizures after Soto. Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L., 27, 16.

Haywood, B. R. (2022). Ending Race-Based Pretextual Stops626: Strategies for Eliminating America’s Most Egregious Police Practice. Rich. Pub. Int. L. Rev., 26, 47.

Pierson E., Simoiu C., Overgoor J., Corbett-Davies S., Jenson D., Shoemaker A., Ramachandran V., Barghouty P., Phillips C., Shroff R., and Goel S. (2020). A large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 7. https://openpolicing.stanford.edu/

New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU). A close look at stop-and-frisk in NYC. NYCLU. Accessed on April 12, 2023. https://www.nyclu.org/en/closer-look-stop-and-frisk-nyc

NYCLU. 2018. “Stop-And-Frisk Data.” New York Civil Liberties Union. December 10, 2018. https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data.

NBC12 Newsroom. (2022). Chesterfield police issue over 560 tickets in Hull Street Road operation. NBC12. Accessed on April 12, 2023. https://www.nbc12.com/2022/06/14/chesterfield-police-issue-over-560-tickets-hull-street-road-operation/

Rizzo, S., Vozzella, L., and Oakford S. (2023). Video shows Va. deputies pile on top of Irvo Otieno before his death. The Washington Post. Accessed on April 12, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/03/20/irvo-otieno-video-virginia-deputies/

Seo, Sarah A.. Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019.